Love it, loathe it, or wonder why the rest of it couldn’t have been as great as the Wonder Woman scenes, Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice is now loosed upon the world. I saw it last week and it’s an interesting movie, far more for what it isn’t as what it is. While it begins in the ruins of Metropolis that Man of Steel created, it’s a very different creature when compared to the previous movie—not just because of the expanded cast or world building but the often very dour tone.

Whether that tonal shift helps the film or not is something the internet is gleefully debating right now. But what I found interesting was how much it helps Man of Steel. I rewatched that before Dawn of Justice and it’s a very different, and in many ways much better, movie than I remember.

A lot of its best moments land in the opening 20 minutes and the hour that follows it. That opening scene sees Jor and Lara, Kal-El’s parents recast as something more than the toga-wearing scientists of every previous iteration. Here they’re physical and ideological rebels as well as intellectual subversives. They, and the Krypton they inhabit, are far more emotional, even volatile, than their predecessors.

Most of that is embodied in Crowe’s surprisingly hands-on Jor-El, a two-fisted scientist of a sort we’ve not seen in these movies before. He gets the heavy lifting to do in terms of the action, and Crowe’s articulate physicality is a really smart choice for Superman’s first father. Ayelet Zurer, who’d go on to do amazing work on Daredevil, has less to do but has more authority as Lara. Jor is in the trenches and pays the price; Lara sees her world end and faces it down, alone and unafraid, in one of the film’s best scenes.

But where this sequence really works is in setting up Michael Shannon’s Zod as a sympathetic monster and a counterpoint to Jor-El. Zod wants to save his people through violent retribution; Jor wants to save the idea of his people through his son. Neither is fully right, both are selfish, and both are the heroes of their own story. They share a desire to facilitate the survival of the Kryptonians but come at it from entirely different directions. As a result their conflict is desperate, untidy, and makes us see the Kryptonians as people rather than an ideal—a race whose story was incomplete and who were unable to continue it, except through the survival of one baby and a prison full of desperate, passionate zealots.

That’s a hell of a setup, and the film uses it as a foundation for a really compelling first hour. Influenced heavily by the excellent, Mark Waid-scripted Superman: Birthright, it intercuts three plots. The first is Clark’s complicated, difficult childhood. The second is his equally difficult, even more solitary adulthood, and the third is Lois Lane demonstrating she’s the best part of the movie.

Let’s start at the end and work forwards. Lois has always been one of the most fun elements of the Superman mythos and, when written well, she’s one of DC’s most iconic characters, male or female. The numerous problems with how Dawn of Justice handles Lois aren’t for this article to discuss, but her actions in Man of Steel are—and they’re often immense fun. The movie uses Lois as a means of showing us Clark’s adult life, and the world he’s grown up into. She’s tracking the wake he leaves; an urban myth of a man who does amazingly heroic, impossible things and then vanishes. It’s the story of her career. It’s also the story of Clark’s life, and by tying these plots together the movie does some really smart narrative crosscutting. We see Clark’s quietly horrific childhood—the struggle he has with his powers and normality and the attempts he’s made to close that circuit—through the lens of Lois’ investigations. Clark’s struggle to be a whole man, let alone a good one, is coded into every script beat in that first hour and it’s really well done, compelling cinema.

That brings us to the scenes dealing with Clark’s childhood, and the massive problem that comes with them. Diane Lane’s Martha Kent plays no part in that. She’s a perfect piece of casting and an island of pragmatic love within the film, just as she is an island of calm for her son’s overloaded senses.

Man of Steel’s Jonathan Kent, played by Kevin Costner, is a different story.

Jonathan is regularly cited as one of the worst elements of the movie. In particular, he’s had all sorts of pretty toxic philosophies hung around his neck, due to his apparent reluctance to let his son save a busload of his friends.

These interpretations are definitely valid, but they’re not ones I subscribe to. For me, the Jonathan scenes live and die on one word, his answer to Clark asking if he should have let the other kids die:

“Maybe.”

You can see him wracked with uncertainty, see the revulsion on his face as he says that word. That liminal space between humanity and the alien, between being a father and being a guardian, is where this version of Jonathan Kent lives and dies. He’s a country farmer, a man who has worked with his hands his entire life and has the pragmatism and conservatism that comes with that experience. But he’s also the adopted father of a boy who is not human.

This is a man with no right answers to cling to. On one hand, telling Clark not to use his abilities will lead to deaths. On the other, having Clark embrace them will make him visible—and, more importantly, different. Jonathan’s dilemma is that of every parent: knowing when to let their child make their own way in the world. But the moment he lets go, he believes, is the moment Clark is exposed to huge danger. More importantly, his son will cease being a man and start being a catalyst for massive change. The very change Jor-El planned for, in fact.

So, Jonathan Kent lives in the only space he can: the temporary now. Everything he does in the movie is about maintaining the status quo—keeping his son normal, keeping him safe, clinging to the narrative of raising a boy in rural Kansas. That’s why he chooses to die, because that will keep Clark hidden just a little while longer. It’s also why he looks so peaceful in his final moments.

All this doesn’t make Jonathan a saint. In fact, it paints him as a borderline abusive figure, albeit one whose behaviour stems from upbringing and worldview rather than malice. More importantly it marks him out as a complicated, untidy, human figure rather than the Randian Bullhorn he’s often seen as being.

So that’s the first hour of the movie: a Wachowski-esque bit of space action, an intrepid reporter, a lonely god and the well-meaning but fundamentally flawed humans who tried their best to raise him. This is about as good a modern version of Superman’s origin as we could possibly hope for, and it’s shot through with a tension that mirrors Clark’s own uncertainty. Crucially as well—it’s not dour. There’s humour and warmth here, and that’s still present even as the movie enters its second and third, deeply troubling act.

The closing action sequence in Man of Steel is so thematically different from the rest of the movie it’s basically Dawn of Justice Act 0—so much so that we see it again from Bruce Wayne’s point of view in the opening minutes of the second movie. It’s far more effective, too, as we get a human view of what happens when gods go to war. In fact, it’s one of the strongest sections of Dawn of Justice and grounds much of Bruce’s plot in the film.

Ironically, it has the exact opposite effect on Clark. There’s no dancing around the damage, and deaths, he’s personally responsible for: Dawn of Justice expressly states that thousands of casualties were caused by this fight. That in itself is horrifying. The fact that at no point does Clark make any attempt to contain the damage is much, much worse—especially after the devastation he helped wreak on Smallville earlier in the movie.

Snyder and Goyer have both talked about this a lot, and to some extent you can see their thinking. Their argument is that this is Clark at the very start of his career, a man barely in control of his powers and reacting far more than taking charge. That’s an interesting and valid take on his story.

The problem with it is that film is the wrong medium to tell that interesting, valid take on his story. The idea of a superhuman exploring the limits and consequences of their strength is amazingly rich material for a TV show to mine. Supergirl, in particular, has been doing an amazing job of telling that story and if you’ve not seen it, do catch up—I can’t recommend the show enough.

But condense that story, as you have to, into a 2+ hours movie and your main character comes off as irresponsible or outright dangerous. That’s why this sequence feels so incongruous: the quiet, compassionate Clark we’ve seen up to this point is replaced with a reactive, barely controlled engine of destruction. Again, I see Goyer and Snyder’s point. But that doesn’t excuse the severe tonal shift or the distanced, uncaring patina it gives Superman…something which Dawn of Justice embraces and severely damages itself in so doing.

The same must be said of his murder of General Zod. Snyder and Goyer can justify this until they’re blue in the face, but no explanation they can offer will be good enough because the perception of this scene is more important than the intent behind it. Because of the three-year gap between movies, and the even wider gap between the perceptions of Snyder and Goyer and those of their audience, this incarnation of Superman will always be associated with murder. That’s something that Dawn of Justice is built on but fails to fully address, sacrificing Clark’s humanity in favour of his near omniscience. It’s not successfully handled in at all, but the issue is at least central to the movie. Here, the final act feels as if Dawn of Justice starts half an hour, and three years, early. Worse, that in doing so it overwrites a quieter, more successful movie.

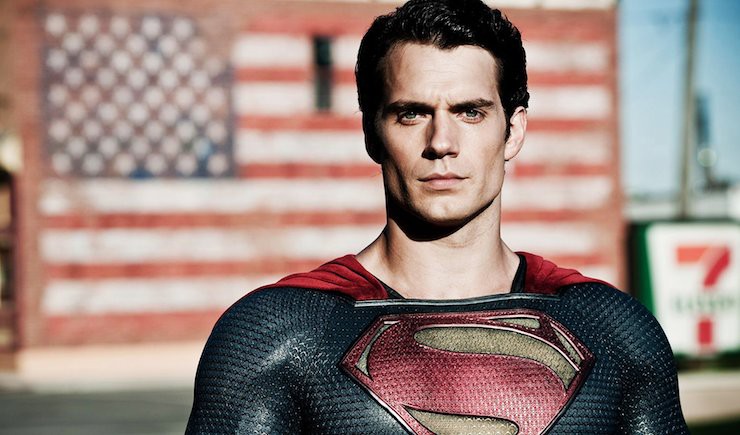

In the post-Dawn of Justice world, Man of Steel is a surprising cinematic curiosity. Where its sequel is built on the stern consequences of power, much of this movie is a pretty well done hero’s journey. Clark, as we first meet him, is a shy, unconfident, country boy who isn’t quite sure where he fits in. That’s a compelling narrative and the very one that drew me to the character years ago. It’s also where Man of Steel and this incarnation of Superman are at their very best; I hope that, once Justice is finished Dawning, it’s also a story we’ll be returning to.

Alasdair Stuart is a freelancer writer, RPG writer and podcaster. He owns Escape Artists, who publish the short fiction podcasts Escape Pod, Pseudopod, Podcastle, Cast of Wonders, and the magazine Mothership Zeta. He blogs enthusiastically about pop culture, cooking and exercise at Alasdairstuart.com, and tweets @AlasdairStuart.